- Home

- Terry Brooks

The Druid of Shannara

The Druid of Shannara Read online

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

AGAINST THE SHADOWEN

MAP

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

CHAPTER XXI

CHAPTER XXII

CHAPTER XXIII

CHAPTER XXIV

CHAPTER XXV

CHAPTER XXVI

CHAPTER XXVII

CHAPTER XXVIII

CHAPTER XXIX

CHAPTER XXX

CHAPTER XXXI

CHAPTER XXXII

CHAPTER XXXIII

JOIN US ONLINE TO FIND OUT . . .

DON’T MISS ONE EXCITING INSTALLMENT . . .

THE BLACK UNICORN

WIZARD AT LARGE

THE TANGLE BOX

WITCHES’ BREW

ALSO BY TERRY BROOKS

COPYRIGHT

To Laurie and Peter,

for their love, support, and encouragement

in all things

AGAINST THE SHADOWEN

Even with the silver dust exploding all through them, the Shadowen came on. Despairing, Cogline used the last of his power, igniting a wall of flame that brought a temporary halt to their advance. Swiftly he darted inside and snatched the Druid history from its place. Now we’ll see!

He barely made the door again before the Shadowen were through the wall and on him. He heard Rimmer Dall screaming at them. There was nowhere to run and no point in trying, so he simply stood his ground, clutching the book to his chest, a scarecrow in tattered robes before a whirlwind. His attackers came on.

When they were on him, as his body was about to be ripped apart, he felt the rune marking on the book flare to life. Brilliant fire burst forth. Everything within fifty feet was consumed. It remains for you now, Walker Boh, was Cogline’s last thought.

He disappeared in the flames.

I

The King of the Silver River stood at the edge of the Gardens that had been his domain since the dawn of the age of faerie and looked out over the world of mortal men. What he saw left him sad and discouraged. Everywhere the land sickened and died, rich black earth turning to dust, grassy plains withering, forests becoming huge stands of deadwood, and lakes and rivers either stagnating or drying away. Everywhere the creatures who lived upon the land sickened and died as well, unable to sustain themselves as the nourishment they relied upon grew poisoned. Even the air had begun to turn foul.

And all the while, the King of the Silver River thought, the Shadowen grow stronger.

His fingers reached out to brush the crimson petals of the cyclamen that grew thick about his feet. Forsythia clustered just beyond, dogwood and cherry farther back, fuchsia and hibiscus, rhododendrons and dahlias, beds of iris, azaleas, daffodils, roses, and a hundred other varieties of flowers and flowering plants that were always in bloom, a profusion of colors that stretched away into the distance until lost from sight. There were animals to be seen as well, both large and small, creatures whose evolution could be traced back to that distant time when all things lived in harmony and peace.

In the present world, the world of the Four Lands and the Races that had evolved out of the chaos and destruction of the Great Wars, that time was all but forgotten. The King of the Silver River was its sole remnant. He had been alive when the world was new and its first creatures were just being born. He had been young then, and there had been many like him. Now he was old and he was the last of his kind. Everything that had been, save for the Gardens in which he lived, had passed away. The Gardens alone survived, changeless, sustained by the magic of faerie. The Word had given the Gardens to the King of the Silver River and told him to tend them, to keep them as a reminder of what had once been and what might one day be again. The world without would evolve as it must, but the Gardens would remain forever the same.

Even so, they were shrinking. It was not so much physical as spiritual. The boundaries of the Gardens were fixed and unalterable, for the Gardens existed in a plane of being unaffected by changes in the world of mortal men. The Gardens were a presence rather than a place. Yet that presence was diminished by the sickening of the world to which it was tied, for the work of the Gardens and their tender was to keep that world strong. As the Four Lands grew poisoned, the work became harder, the effects of that work grew shorter, and the boundaries of human belief and trust in its existence—always somewhat marginal—began to fail altogether.

The King of the Silver River grieved that this should be. He did not grieve for himself; he was beyond that. He grieved for the people of the Four Lands, the mortal men and women for whom the magic of faerie was in danger of being lost forever. The Gardens had been their haven in the land of the Silver River for centuries, and he had been the spirit friend who protected its people. He had watched over them, had given them a sense of peace and well-being that transcended physical boundaries, and gave promise that benevolence and goodwill were still accessible in some corners of the world to all. Now that was ended. Now he could protect no one. The evil of the Shadowen, the poison they had inflicted upon the Four Lands, had eroded his own strength until he was virtually sealed within his Gardens, powerless to go to the aid of those he had worked so long to protect.

He stared out into the ruin of the world for a time as his despair worked its relentless will on him. Memories played hide-and-seek in his mind. The Druids had protected the Four Lands once. But the Druids were gone. A handful of descendents of the Elven house of Shannara had been champions of the Races for generations, wielding the remnants of the magic of faerie. But they were all dead.

He forced his despair away, replacing it with hope. The Druids could come again. And there were new generations of the old house of Shannara. The King of the Silver River knew most of what was happening in the Four Lands even if he could not go out into them. Allanon’s shade had summoned a scattering of Shannara children to recover the lost magic, and perhaps they yet would if they could survive long enough to find a means to do so. But all of them had been placed in extreme peril. All were in danger of dying, threatened in the east, south, and west by the Shadowen and in the north by Uhl Belk, the Stone King.

The old eyes closed momentarily. He knew what was needed to save the Shannara children—an act of magic, one so powerful and intricate that nothing could prevent it from succeeding, one that would transcend the barriers that their enemies had created, that would break past the screen of deceit and lies that hid everything from the four on whom so much depended.

Yes, four, not three. Even Allanon did not understand the whole of what was meant to be.

He turned and made his way back toward the center of his refuge. He let the songs of the birds, the fragrances of the flowers, and the warmth of the air soothe him as he walked and he drew in through his senses the color and taste and feel of all that lay about him. There was virtually nothing that he could not do within his Gardens. Yet his magic was needed without. He knew what was required. In preparation he took the form of the old man that showed himself occasionally to the world beyond. His gait became an unsteady shamble, his breathing wheezed, his eyes dimmed, and his body ached with the feelings of life fading. The birdsong stopped, and the small animals that had crowded close edged quickly away. He forced himself to separate fro

m everything he had evolved into, receding into what he might have been, needing momentarily to feel human mortality in order to know better how to give that part of himself that was needed.

When he reached the heart of his domain, he stopped. There was a pond of clearest water fed by a small stream. A unicorn drank from it. The earth that cradled the pond was dark and rich. Tiny, delicate flowers that had no name grew at the water’s edge; they were the color of new snow. A small, intricately formed tree lifted out of a scattering of violet grasses at the pond’s far end, its delicate green leaves laced with red. From a pair of massive rocks, streaks of colored ore shimmered brightly in the sunshine.

The King of the Silver River stood without moving in the presence of the life that surrounded him and willed himself to become one with it. When he had done so, when everything had threaded itself through the human form he had taken as if joined by bits and pieces of invisible lacing, he reached out to gather it all in. His hands, wrinkled human skin and brittle bones, lifted and summoned his magic, and the feelings of age and time that were the reminders of mortal existence disappeared.

The little tree came to him first, uprooted, transported, and set down before him, the framework of bones on which he would build. Slowly it bent to take the shape he desired, leaves folding close against the branches, wrapping and sealing away. The earth came next, handfuls lifted by invisible scoops to place against the tree, padding and defining. Then came the ores for muscle, the waters for fluids, and the petals of the tiny flowers for skin. He gathered silk from the unicorn’s mane for hair and black pearls for eyes. The magic twisted and wove, and slowly his creation took form.

When he was finished, the girl who stood before him was perfect in every way but one. She was not yet alive.

He cast about momentarily, then selected the dove. He took it out of the air and placed it still living inside the girl’s breast where it became her heart. Quickly he moved forward to embrace her and breathed his own life into her. Then he stepped back to wait.

The girl’s breast rose and fell, and her limbs twitched. Her eyes fluttered open, coal black as they peered out from her delicate white features. She was small boned and finely wrought like a piece of paper art smoothed and shaped so that the edges and corners were replaced by curves. Her hair was so white it seemed silver; there was a glitter to it that suggested the presence of that precious metal.

“Who am I?” she asked in a soft, lilting voice that whispered of tiny streams and small night sounds.

“You are my daughter,” the King of the Silver River answered, discovering within himself the stirring of feelings he had thought long since lost.

He did not bother telling her that she was an elemental, an earth child created of his magic. She could sense what she was from the instincts with which he had endowed her. No other explanation was needed.

She took a tentative step forward, then another. Finding that she could walk, she began to move more quickly, testing her abilities in various ways as she circled her father, glancing cautiously, shyly at the old man as she went. She looked around curiously, taking in the sights, smells, sounds, and tastes of the Gardens, discovering in them a kinship that she could not immediately explain.

“Are these Gardens my mother?” she asked suddenly, and he told her they were. “Am I a part of you both?” she asked, and he told her yes.

“Come with me,” he said gently.

Together, they walked through the Gardens, exploring in the manner of a parent and child, looking into flowers, watching for the quick movement of birds and animals, studying the vast, intricate designs of the tangled undergrowth, the complex layers of rock and earth, and the patterns woven by the threads of the Gardens’ existence. She was bright and quick, interested in everything, respectful of life, caring. He was pleased with what he saw; he found that he had made her well.

After a time, he began to show her something of the magic. He demonstrated his own first, only the smallest bits and pieces of it so as not to overwhelm her. Then he let her test her own against it. She was surprised to learn that she possessed it, even more surprised to discover what it could do. But she was not hesitant about using it. She was eager.

“You have a name,” he told her. “Would you like to know what it is?”

“Yes,” she answered, and stood looking at him alertly.

“Your name is Quickening.” He paused. “Do you understand why?”

She thought a moment. “Yes,” she answered again.

He led her to an ancient hickory whose bark peeled back in great, shaggy strips from its trunk. The breezes cooled there, smelling of jasmine and begonia, and the grass was soft as they sat together. A griffin wandered over through the tall grasses and nuzzled the girl’s hand.

“Quickening,” the King of the Silver River said. “There is something you must do.”

Slowly, carefully he explained to her that she must leave the Gardens and go out into the world of men. He told her where it was that she must go and what it was that she must do. He talked of the Dark Uncle, the Highlander, and the nameless other, of the Shadowen, of Uhl Belk and Eldwist, and of the Black Elfstone. As he spoke to her, revealing the truth behind who and what she was, he experienced an aching within his breast that was decidedly human, part of himself that had been submerged for many centuries. The ache brought a sadness that threatened to cause his voice to break and his eyes to tear. He stopped once in surprise to fight back against it. It required some effort to resume speaking. The girl watched him without comment—intense, introspective, expectant. She did not argue with what he told her and she did not question it. She simply listened and accepted.

When he was done, she stood up. “I understand what is expected of me. I am ready.”

But the King of the Silver River shook his head. “No, child, you are not. You will discover that when you leave here. Despite who you are and what you can do, you are vulnerable nevertheless to things against which I cannot protect you. Be careful then to protect yourself. Be on guard against what you do not understand.”

“I will,” she replied.

He walked with her to the edge of the Gardens, to where the world of men began, and together they stared out at the encroaching ruin. They stood without speaking for a very long time before she said, “I can tell that I am needed there.”

He nodded bleakly, feeling the loss of her already though she had not yet departed. She is only an elemental, he thought and knew immediately that he was wrong. She was a great deal more. As much as if he had given birth to her, she was a part of him.

“Goodbye, Father,” she said suddenly and left his side.

She walked out of the Gardens and disappeared into the world beyond. She did not kiss him or touch him in parting. She simply left, because that was all she knew to do.

The King of the Silver River turned away. His efforts had wearied him, had drained him of his magic. He needed time to rest. Quickly he shed his human image, stripping away the false covering of skin and bones, washing himself clean of its memories and sensations, and reverting to the faerie creature he was.

Even so, what he felt for Quickening, his daughter, the child of his making, stayed with him.

II

Walker Boh came awake with a shudder.

Dark Uncle.

The whisper of a voice in his mind jerked him back from the edge of the black pool into which he was sliding, pulled him from the inky dark into the gray fringes of the light, and he started so violently that the muscles of his legs cramped. His head snapped up from the pillow of his arm, his eyes slipped open, and he stared blankly ahead. There was pain all through his body, endless waves of it. The pain wracked him as if he had been touched by a hot iron, and he curled tightly into himself in a futile effort to ease it. Only his right arm remained outstretched, a heavy and cumbersome thing that no longer belonged to him, fastened forever to the floor of the cavern on which he lay, turned to stone to the elbow.

The source of the pain

was there.

He closed his eyes against it, willing it to disperse, to disappear. But he lacked the strength to command it, his magic almost gone, dissipated by his struggle to resist the advancing poison of the Asphinx. It was seven days now since he had come into the Hall of Kings in search of the Black Elfstone, seven days since he had found instead the deadly creature that had been placed there to snare him.

Oh, yes, he thought feverishly. Definitely to snare him.

But by whom? By the Shadowen or by someone else? Who now had possession of the Black Elfstone?

He recalled in despair the events that had brought him to this end. There had been the summons from the shade of Allanon, dead three hundred years, to the heirs of the Shannara magic: his nephew Par Ohmsford, his cousin Wren Ohmsford, and himself. They had received the summons and a visit from the once-Druid Cogline urging them to heed it. They had done so, assembling at the Hadeshorn, ancient resting place of the Druids, where Allanon had appeared to them and charged them with separate undertakings that were meant to combat the dark work of the Shadowen who were using magic of their own to steal away the life of the Four Lands. Walker had been charged with recovering Paranor, the disappeared home of the Druids, and with bringing back the Druids themselves. He had resisted this charge until Cogline had come to him again, this time bearing a volume of the Druid Histories which told of a Black Elfstone which had the power to retrieve Paranor. That in turn had led him to the Grimpond, seer of the earth’s and mortal men’s secrets.

He searched the gloom of the cavern about him, the doors to the tombs of the Kings of the Four Lands dead all these centuries, the wealth piled before the crypts in which they lay, and the stone sentinels that kept watch over their remains. Stone eyes stared out of blank faces, unseeing, unheeding. He was alone with their ghosts.

He was dying.

Tears filled his eyes, blinding him as he fought to hold them back. He was such a fool!

Dark Uncle. The words echoed soundlessly, a memory that taunted and teased. The voice was the Grimpond’s, that wretched, insidious spirit responsible for what had befallen him. It was the Grimpond’s riddles that had led him to the Hall of Kings in search of the Black Elfstone. The Grimpond must have known what awaited him, that there would be no Elfstone but the Asphinx instead, a deadly trap that would destroy him.

The Talismans of Shannara

The Talismans of Shannara The Sword of Shannara: The Druids' Keep: The Druids' Keep

The Sword of Shannara: The Druids' Keep: The Druids' Keep Witch Wraith

Witch Wraith The Elf Queen of Shannara

The Elf Queen of Shannara The Weapons Master's Choice

The Weapons Master's Choice The Scions of Shannara

The Scions of Shannara Armageddon's Children

Armageddon's Children The Sword of Shannara Trilogy the Sword of Shannara Trilogy

The Sword of Shannara Trilogy the Sword of Shannara Trilogy The Darkling Child

The Darkling Child The Black Unicorn

The Black Unicorn The High Druid's Blade

The High Druid's Blade Wards of Faerie

Wards of Faerie The Tangle Box

The Tangle Box The Black Elfstone

The Black Elfstone The Black Irix

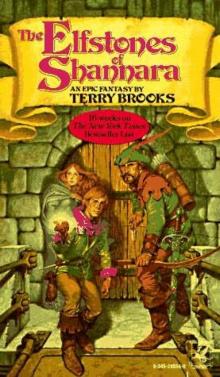

The Black Irix The Elfstones of Shannara

The Elfstones of Shannara The Magic Kingdom of Landover Volume 2

The Magic Kingdom of Landover Volume 2 Bearers of the Black Staff

Bearers of the Black Staff Jarka Ruus

Jarka Ruus The Druid of Shannara

The Druid of Shannara The Sword of Shannara

The Sword of Shannara The High Druid of Shannara Trilogy

The High Druid of Shannara Trilogy Angel Fire East

Angel Fire East The Gypsy Morph

The Gypsy Morph The Wishsong of Shannara

The Wishsong of Shannara Magic Kingdom for Sale--Sold

Magic Kingdom for Sale--Sold Running With the Demon

Running With the Demon Wizard at Large

Wizard at Large The Sorcerer's Daughter

The Sorcerer's Daughter Imaginary Friends

Imaginary Friends The Elves of Cintra

The Elves of Cintra Tanequil

Tanequil Witches' Brew

Witches' Brew The Sword of the Shannara and the Elfstones of Shannara

The Sword of the Shannara and the Elfstones of Shannara The World of Shannara

The World of Shannara A Princess of Landover

A Princess of Landover A Knight of the Word

A Knight of the Word Straken

Straken The Skaar Invasion

The Skaar Invasion The Measure of the Magic: Legends of Shannara

The Measure of the Magic: Legends of Shannara Ilse Witch

Ilse Witch Bloodfire Quest

Bloodfire Quest The Stiehl Assassin

The Stiehl Assassin Antrax

Antrax The Last Druid

The Last Druid Paladins of Shannara: Allanon's Quest

Paladins of Shannara: Allanon's Quest Sometimes the Magic Works: Lessons From a Writing Life

Sometimes the Magic Works: Lessons From a Writing Life Wards of Faerie: The Dark Legacy of Shannara

Wards of Faerie: The Dark Legacy of Shannara Indomitable: The Epilogue to The Wishsong of Shannara

Indomitable: The Epilogue to The Wishsong of Shannara Heritage of Shannara 01 - The Druid of Shannara

Heritage of Shannara 01 - The Druid of Shannara Star Wars - Phantom Menace

Star Wars - Phantom Menace The Dark Legacy of Shannara Trilogy 3-Book Bundle

The Dark Legacy of Shannara Trilogy 3-Book Bundle The Bloodfire Quest

The Bloodfire Quest The Hook (1991)

The Hook (1991) Star Wars: Episode I: The Phantom Menace

Star Wars: Episode I: The Phantom Menace Street Freaks

Street Freaks The Sword of Shannara & Elfstones of Shannara

The Sword of Shannara & Elfstones of Shannara The Magic Kingdom of Landover , Volume 1

The Magic Kingdom of Landover , Volume 1 The Phantom Menace

The Phantom Menace Unfettered

Unfettered Allanon's Quest

Allanon's Quest Paladins of Shannara: The Weapons Master's Choice

Paladins of Shannara: The Weapons Master's Choice Terry Brooks - Paladins of Shannara - Allanon's Quest (Short Story)

Terry Brooks - Paladins of Shannara - Allanon's Quest (Short Story) Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (star wars)

Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (star wars) Warrior (The Word and the Void)

Warrior (The Word and the Void) Word & Void 03 - Angel Fire East

Word & Void 03 - Angel Fire East![[Magic Kingdom of Landover 05] - Witches' Brew Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/05/magic_kingdom_of_landover_05_-_witches_brew_preview.jpg) [Magic Kingdom of Landover 05] - Witches' Brew

[Magic Kingdom of Landover 05] - Witches' Brew The Magic Kingdom of Landover - Volume 2

The Magic Kingdom of Landover - Volume 2 The Measure of the Magic

The Measure of the Magic The First King of Shannara

The First King of Shannara Sometimes the Magic Works

Sometimes the Magic Works The Sword of Shannara, Part 2: The Druids' Keep

The Sword of Shannara, Part 2: The Druids' Keep The Sword of Shannara tost-1

The Sword of Shannara tost-1 Paladins of Shannara: The Black Irix (Short Story)

Paladins of Shannara: The Black Irix (Short Story) Tangle Box

Tangle Box Word & Void 02 - A Knight of the Word

Word & Void 02 - A Knight of the Word The Sword of Shannara, Part 1: In the Shadow of the Warlock Lord

The Sword of Shannara, Part 1: In the Shadow of the Warlock Lord The Wishsong of Shannara tost-3

The Wishsong of Shannara tost-3 The Elfstones of Shannara tost-2

The Elfstones of Shannara tost-2