- Home

- Terry Brooks

Angel Fire East Page 5

Angel Fire East Read online

Page 5

If the temperature dropped and the forecast for snow proved out, both would be open by tomorrow night.

She hiked deliberately toward the cliffs, passing through a familiar stand of spruce clustered just beyond the backstop of the nearest baseball diamond, and Pick dropped from its branches onto her shoulder.

“You took your sweet time getting out here!” he snapped irritably, settling himself in place against the down folds of her collar.

“Church ran a little long,” she replied, refusing to be baited. Pick was always either irritable or coming up on it, so she was used to his abrupt pronouncements and sometimes scathing rebukes. “You probably got a lot done without me anyway.”

“That’s not the point!” he snapped. “When you make a commitment—”

“—you stick to it,” she finished, having heard this chestnut at least a thousand times. “But I can’t ignore the rest of my life, either.”

Pick muttered something unintelligible and squirmed restlessly. A hundred and sixty-five years old, he was a sylvan, a forest creature composed of sticks and moss, conceived by magic, and born in a pod. In every woods and forest in the world, sylvans worked to balance the magic that was centered there so that all living things could coexist in the way the Word had intended. It was not an easy job and not without its disappointments; many species had been lost through natural evolution or the depredations of humans. Even woods and forests were destroyed, taking with them all the creatures who lived there, including the sylvans who tended them. Erosion of the forest magic over the passing of the centuries had been slow, but steady, and Pick declared often and ominously that time was running out.

“The park looks pretty good,” she offered, banishing such thoughts from her mind, trying to put a positive spin on things for the duration of her afternoon.

Pick was having none of it. “Appearances are deceiving. There’s trouble brewing.”

“Trouble of what sort?”

“Ha! You haven’t even noticed, have you?”

“Why don’t you just tell me?”

They crossed the entry road and walked up toward the turnaround at the west end that overlooked the Rock River from the edge of the bluffs. Beyond the chain-link fence marking the park’s farthest point lay Riverside Cemetery. She had not been out to the graves of her mother or grandparents in more than a week, and she felt a pang of guilt at her oversight.

“The feeders have been out,” Pick advised with a grunt, “skulking about the park in more numbers than I’ve seen in a long time.”

“How many?”

“Lots. Too many to count. Something’s got them stirred up, and I don’t know what it is.”

Shadowy creatures that lurked on the edges of people’s lives, feeders lapped up the energy given off by expenditure of emotions. The darker and stronger the emotions, the greater the number of feeders who gathered to feast. Parasitic beings who responded to their instincts, they did not judge and they did not make choices. Most humans never saw them, except when death came violently and unexpectedly, and they were the last image to register before the lights went out for good. Only those like Nest, who were born with magic themselves, knew there were feeders out there.

Pick gave her a sharp look, his pinched wooden face all wizened and rough, his gnarled limbs drawn up about his crooked body so that he took on the look of a bird’s nest. His strange, flat eyes locked on her. “You know something about this, don’t you?”

She nodded. “Maybe.”

She told him about Findo Gask and the possibility that John Ross was returning to Hopewell. “A demon’s presence would account for all the feeders, I expect,” she finished.

They walked up through the playground equipment and picnic tables that occupied the wooded area situated across the road from the Indian mounds and the bluffs. When they reached the turnaround, she slowed, suddenly aware that Pick hadn’t spoken a word since she had told him about Findo Gask and John Ross. He hadn’t even told her what work he wanted her to do that day in the park.

“What do you think?” she asked, trying to draw him out.

He sat motionless on her shoulder, silent and remote. She crossed the road to the edge of the bluffs and moved out to where she could see the frozen expanse of the Rock River. Even with the warmer temperatures of the past few days, the bayou that lay between the near shore and the raised levee on which the railroad tracks had been laid remained frozen. Beyond, where the wider channel opened south on its way to the Mississippi, the Rock was patchy with ice, the swifter movement of the water keeping the river from freezing over completely. That would change when January arrived.

“Another demon,” Pick said softly. “You’d think one in a lifetime would be enough.”

She nodded wordlessly, eyes scanning the tangle of tree trunks and limbs immediately below, searching for movement in the lengthening shadows. The feeders, if they were out yet, would be there, watching.

“Some sylvans go through their entire lives and never encounter a demon.” Pick’s voice was soft and contemplative. “Hundreds of years, and not a one.”

“It’s my fault,” she said.

“Not hardly!”

“It is,” she insisted. “It began with my father.”

“Which was your grandmother’s mistake!” he snapped.

She glanced down at him, all fiery-eyed and defensive of her, and she gave him a smile. “Where would I be without you, Pick?”

“Somewhere else, I expect.”

She sighed. Over the past fifteen years she had attempted to move away from the park. To leave the park was unthinkable for Pick; the park was his home and his charge. For the sylvan, nothing else existed. It was different for her, of course, but Pick didn’t see it that way. Pick saw things in black-and-white terms. Even an inherited obligation—in this case, an obligation passed down through six generations of Freemark women to help care for the park—wasn’t to be ignored, no matter what. She belonged here, working with him, keeping the magic in balance and looking after the park. But this was all Pick knew. It was all he had done for more than one hundred fifty years. Nest didn’t have one hundred fifty years, and she wasn’t so sure that tending the magic and looking after the park was what she wanted to spend the rest of her life doing.

She looked off across the Rock River, at the hazy midafternoon twilight beginning to steal out of the east as the shortened winter day slipped westward. “What do you want to do today, Pick?” she asked quietly.

He shrugged. “Too late to do much, I expect.” He did not say it in a gruff way; he simply sounded resigned. “Let’s just have a look around, see if anything needs doing, and we can see to it tomorrow.” He sniffed and straightened. “If you think you can spare the time, of course.”

“Of course,” she echoed.

They left the bluffs and walked down the road from the turnaround to where it split, one branch doubling back under a bridge to descend to the base of the bluffs and what she thought of as the feeder caves, the other continuing on along the high ground to the east end of the park, where the bulk of the woods and picnic areas were located. They followed the latter route, working their way along the fringes of the trees, taking note of how everything was doing, not finding much that didn’t appear as it should. The park was in good shape, even if Pick wasn’t willing to acknowledge as much. Winter had put her to sleep in good order, and the magic, dormant and restful in the long, slow passing of the season, was in perfect balance.

The world of Sinnissippi Park is at peace, Nest thought to herself, glancing off across the open flats of the ball diamonds and playgrounds and through the skeletal trees and rolling stretches of woodland. Why couldn’t her world be the same?

But she knew the answer to that question. She had known it for a long time. The answer was Wraith.

Three years earlier, she had been acclaimed as the greatest American long-distance runner of all time. She had already competed in one Olympics and had won a pair of gold medals and set two wor

ld records. She had won thirty-two consecutive races since. She owned a combined eight world titles in the three and five thousand. She was competing in her second Olympics, and she had won the three by such a wide margin that a double in the five seemed almost a given.

She remembered that last race vividly. She had watched the video a thousand times. She could replay it in her own mind from memory, every moment, frame by frame.

Looking off into the trees, she did so now.

She breaks smoothly from the start line, content to stay with the pack for several laps, for this longer distance places a higher premium on patience and endurance than on speed. There are eight lead changes in the first two thousand meters, and then her competitors begin boxing her in. Working in shifts, the Ukrainians, the Ethiopians, a Moroccan, and a Spaniard pin her against the inside of the track. She has gone undefeated in the three- and five-thousand-meter events for four years. You don’t do that, no matter how well liked or respected you are, and not make enemies. In any case, she has never been all that close to the other athletes. She trains with her college coach or alone. She stays by herself when she travels to events. She keeps apart because of the nature of her life. She is careful not to get too close to anyone. Her legacy of magic has made her wary.

With fifteen hundred meters to go, she is locked in the middle of a pack of runners and unable to break free.

At the thousand-meter mark, a scuffle for position ensues, and she is pushed hard, loses her balance, and tumbles from the track.

She comes back to her feet almost as quickly as she has gone down and regains the track. Furious at being trapped, jostled, and knocked sprawling, she gives chase, unaware that she is bleeding profusely from a spike wound on her ankle. Zoning into that place where she sometimes goes when she runs, where there is only the sound of her breathing and beat of her heart, she catches and passes the pack. She doesn’t just draw up on them gradually; she runs them down. There is something raw and primal working inside her as she cranks up her speed a notch at a time. The edges of her vision turn red and fuzzy, her breathing burns in her throat like fire, and the pumping of her arms and legs threatens to tear her body apart.

She is running with such determination and with so little regard for herself that she fails to realize that something is wrong.

Then she hears the gasps of the Ethiopians as she passes them in the three and four positions and sees the look of horror on the face of the Spaniard when she catches her two hundred meters from the finish.

A tiger-striped face surges in the air before her, faintly visible in the shimmer of heat and dust. Wraith is emerging from her body. He is breaking free, coming out of her, unbidden and out of control. Wraith, formed of her father’s demon magic and bequeathed to her as a child. Wraith, created as her protector, but become a presence that threatens in ways she can barely tolerate. Wraith, who lives inside her now, a magic she cannot rid herself of and therefore must work constantly to conceal.

It happens all at once. Emerging initially as a faint image that clings to her in a shimmer of light, he begins to take recognizable shape. Only those who are close can see what is happening, and even they are unsure. But their uncertainty is only momentary. If he comes out of her all the way, there will be no more doubt. If he breaks free entirely, he may attack the other runners.

She fights to regain control of him, desperate to do so, unable to understand why he would appear when she has not summoned him and is not threatened with harm.

Powering down the straightaway, her body wracked by pain and fatigue and by her struggle to rein in the ghost wolf, she catches the Moroccan at fifty meters. The Moroccan’s intense, frightened eyes momentarily lock on her as she powers past. Nest’s teeth are bared and Wraith surges in and out of her skin in a flurry of small, quick movements, his terrifying visage flickering in the bright sunlight like an iridescent mirage. The Moroccan swerves from both in terror, and Nest is alone in the lead.

She crosses the finish line first, the winner of the gold medal by ten meters. She knows it is the end of her career, even before the questions on how she could have recovered from her fall and gone on to win turn to rumors on the use of performance-enhancing drugs. Her control over Wraith, always tenuous at best, has eroded further, and she does not understand why. His presence is bearable when she can rely on keeping him in check. But if he can appear anytime she loses control of her emotions, it marks the end of her competitive running days as surely as sunset does the coming of night.

“I’m getting old,” Pick said suddenly, kicking at her shoulder in what she supposed was frustration.

“You’ve always been old,” she reminded him. “You were old when I was born. You’ve already lived twice as long as most humans.”

He glared at her, but said nothing.

She watched clouds fill the edges of the western sky beyond the scraggly tops of the bare hardwoods, rolling out of the plains. The expected storm was on its way. She could feel a drop in the temperature, a bite in the wind that gusted out of the shadows. She pulled the parka tight against her body and zipped it up.

“Hard freeze coming in,” Pick said from his perch on her shoulder. “Let’s give it up for today.”

She turned and began the long walk home. Dead leaves rustled in dry clusters against the bare ground and the trunks of trees. She kicked at pieces of deadwood, her thoughts moody and unsettled, fragments of the race and its aftermath still playing out in her mind.

It had taken months to put an end to the newspaper reports, even after she had taken a voluntary drug test in an effort to end the speculation. Everyone wanted to know why she would quit competitive running when she was at the peak of her career, when she was so young, after she had won so often. She had given interviews freely on the subject for months, and finally she had just given up. She couldn’t explain it to them, of course. She couldn’t begin to make them understand. She couldn’t tell them about the magic or Wraith. She could only say she was tired of running and wanted to do something else. She could only repeat herself, over and over and over again.

Only a month ago, she had received a phone call from an editor at the sports magazine Paul worked for. The editor told her the magazine wanted to do a story on her. She reminded him she didn’t give interviews anymore.

“Change your policy, Nest,” he pressed. “Next summer is the Olympics. People want to know if you’ll come out of retirement and run again. You’re the greatest long-distance runner in your country’s history—you can’t pretend that doesn’t mean something. How about it?”

“No, thanks.”

“Why? Does it have anything to do with your quitting competitive running after your race in the five thousand in the last Olympics? Does it have anything to do with the rumors of drug use? There was a lot of speculation about what happened—”

She’d hung up on him abruptly. He hadn’t called back.

In truth, quitting was the hardest thing she had ever done. She loved the competition. She loved how being the best made her feel. She couldn’t deny giving it up took something away from her, that it hollowed her out. She still trained, because she couldn’t imagine life without the sort of discipline and order that training demanded. She stayed fit and strong, and every so often she would sneak back into the city and have herself timed by her old coach. She did it out of pride and a need to know she was still worth something.

Her life had been a mixed bag since. She lived comfortably enough on money she had saved from endorsements and appearance fees, earning a little extra now and then by writing articles for the running magazines. The writing didn’t pay her much, but it gave her something to do. Something besides helping Pick with the park. Something besides charity and church work. Something besides sitting around remembering her marriage to Paul and how it had fallen apart.

She crossed out of the ravine that divided the bulk of the park from the deep woods and climbed the slope toward the toboggan slide and the pavilion. From out of the distance came the

piercing wail of a freight-train whistle followed by the slow, thunderous buildup of engines and wheels. She paused to look south, seeing the long freight drive out of the west toward Chicago, stark and lonely against the empty expanse of the winter landscape.

She waited until it passed, then continued on. Oddly enough, Pick hadn’t said a word in complaint. Perhaps he sensed her sadness. Perhaps he was wrestling with concerns of his own. She let him be, striding across the open ball diamonds toward the service road and the hedgerow that marked the boundary between the park and her backyard. Pick left her somewhere along the way. Lost in thought, she didn’t see him go. She just looked down and he wasn’t there.

As she crossed the yard Hawkeye skittered along the rear of the house, stalking something Nest couldn’t see. A big, orange stray who had adopted her, he was the sort of cat who put up with you if you fed him and expected you to stay out of his way the rest of the time. She liked having a mouser about, but Hawkeye made her nervous. His name came from the way he looked at her, which she caught him doing all the time. It was a sort of sideways stare, full of trickery and cool appraisal. Pick said he was just trying to figure out how to turn her into dinner.

As she came up beside the garage, she saw a young woman and a little girl sitting on her back steps. The little girl was bundled in an old, shabby red parka with the hood drawn up. Her face was bent toward a rag doll she held protectively in her lap. The woman was barely out of her teens, if that, short and slender with long, tangled dark hair spilling down over her shoulders. She wore a leather biker’s jacket over a mini-skirt and high boots. No gloves, no hat, no scarf.

Her head came up at Nest’s approach, and she climbed to her feet watchfully. The pale afternoon light glinted dully off the silver rings that pierced her ears, nose, and one eyebrow. The deep blue markings of a tattoo darkened the back of one hand where it folded into the other to ward off the cold.

The Talismans of Shannara

The Talismans of Shannara The Sword of Shannara: The Druids' Keep: The Druids' Keep

The Sword of Shannara: The Druids' Keep: The Druids' Keep Witch Wraith

Witch Wraith The Elf Queen of Shannara

The Elf Queen of Shannara The Weapons Master's Choice

The Weapons Master's Choice The Scions of Shannara

The Scions of Shannara Armageddon's Children

Armageddon's Children The Sword of Shannara Trilogy the Sword of Shannara Trilogy

The Sword of Shannara Trilogy the Sword of Shannara Trilogy The Darkling Child

The Darkling Child The Black Unicorn

The Black Unicorn The High Druid's Blade

The High Druid's Blade Wards of Faerie

Wards of Faerie The Tangle Box

The Tangle Box The Black Elfstone

The Black Elfstone The Black Irix

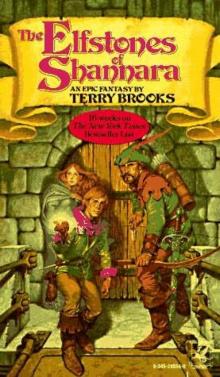

The Black Irix The Elfstones of Shannara

The Elfstones of Shannara The Magic Kingdom of Landover Volume 2

The Magic Kingdom of Landover Volume 2 Bearers of the Black Staff

Bearers of the Black Staff Jarka Ruus

Jarka Ruus The Druid of Shannara

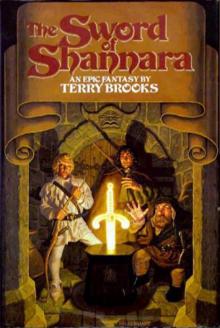

The Druid of Shannara The Sword of Shannara

The Sword of Shannara The High Druid of Shannara Trilogy

The High Druid of Shannara Trilogy Angel Fire East

Angel Fire East The Gypsy Morph

The Gypsy Morph The Wishsong of Shannara

The Wishsong of Shannara Magic Kingdom for Sale--Sold

Magic Kingdom for Sale--Sold Running With the Demon

Running With the Demon Wizard at Large

Wizard at Large The Sorcerer's Daughter

The Sorcerer's Daughter Imaginary Friends

Imaginary Friends The Elves of Cintra

The Elves of Cintra Tanequil

Tanequil Witches' Brew

Witches' Brew The Sword of the Shannara and the Elfstones of Shannara

The Sword of the Shannara and the Elfstones of Shannara The World of Shannara

The World of Shannara A Princess of Landover

A Princess of Landover A Knight of the Word

A Knight of the Word Straken

Straken The Skaar Invasion

The Skaar Invasion The Measure of the Magic: Legends of Shannara

The Measure of the Magic: Legends of Shannara Ilse Witch

Ilse Witch Bloodfire Quest

Bloodfire Quest The Stiehl Assassin

The Stiehl Assassin Antrax

Antrax The Last Druid

The Last Druid Paladins of Shannara: Allanon's Quest

Paladins of Shannara: Allanon's Quest Sometimes the Magic Works: Lessons From a Writing Life

Sometimes the Magic Works: Lessons From a Writing Life Wards of Faerie: The Dark Legacy of Shannara

Wards of Faerie: The Dark Legacy of Shannara Indomitable: The Epilogue to The Wishsong of Shannara

Indomitable: The Epilogue to The Wishsong of Shannara Heritage of Shannara 01 - The Druid of Shannara

Heritage of Shannara 01 - The Druid of Shannara Star Wars - Phantom Menace

Star Wars - Phantom Menace The Dark Legacy of Shannara Trilogy 3-Book Bundle

The Dark Legacy of Shannara Trilogy 3-Book Bundle The Bloodfire Quest

The Bloodfire Quest The Hook (1991)

The Hook (1991) Star Wars: Episode I: The Phantom Menace

Star Wars: Episode I: The Phantom Menace Street Freaks

Street Freaks The Sword of Shannara & Elfstones of Shannara

The Sword of Shannara & Elfstones of Shannara The Magic Kingdom of Landover , Volume 1

The Magic Kingdom of Landover , Volume 1 The Phantom Menace

The Phantom Menace Unfettered

Unfettered Allanon's Quest

Allanon's Quest Paladins of Shannara: The Weapons Master's Choice

Paladins of Shannara: The Weapons Master's Choice Terry Brooks - Paladins of Shannara - Allanon's Quest (Short Story)

Terry Brooks - Paladins of Shannara - Allanon's Quest (Short Story) Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (star wars)

Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (star wars) Warrior (The Word and the Void)

Warrior (The Word and the Void) Word & Void 03 - Angel Fire East

Word & Void 03 - Angel Fire East![[Magic Kingdom of Landover 05] - Witches' Brew Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/05/magic_kingdom_of_landover_05_-_witches_brew_preview.jpg) [Magic Kingdom of Landover 05] - Witches' Brew

[Magic Kingdom of Landover 05] - Witches' Brew The Magic Kingdom of Landover - Volume 2

The Magic Kingdom of Landover - Volume 2 The Measure of the Magic

The Measure of the Magic The First King of Shannara

The First King of Shannara Sometimes the Magic Works

Sometimes the Magic Works The Sword of Shannara, Part 2: The Druids' Keep

The Sword of Shannara, Part 2: The Druids' Keep The Sword of Shannara tost-1

The Sword of Shannara tost-1 Paladins of Shannara: The Black Irix (Short Story)

Paladins of Shannara: The Black Irix (Short Story) Tangle Box

Tangle Box Word & Void 02 - A Knight of the Word

Word & Void 02 - A Knight of the Word The Sword of Shannara, Part 1: In the Shadow of the Warlock Lord

The Sword of Shannara, Part 1: In the Shadow of the Warlock Lord The Wishsong of Shannara tost-3

The Wishsong of Shannara tost-3 The Elfstones of Shannara tost-2

The Elfstones of Shannara tost-2